Overview

The education landscape in India has undergone significant changes over the last two decades. In 2009, the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act ensured that increasing numbers of children enroll in and complete elementary school. In 2020, a new National Education Policy (NEP) reimagined and reorganized the education system, including mandating a new ‘foundational’ stage of education during which children participate in 2 years of pre-primary education, enter primary school at age 6, and acquire foundational literacy and numeracy skills by Grade 2 or 3. In this changing landscape, it is important to review how far we have come, and work towards solutions that can support progress in schooling and learning in the years ahead.

About ASER

Regular collection of rigorous, easy to understand and actionable data is a step in this direction. Every year from 2005 to 2014, and then every alternate year from 2016, the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) has generated estimates of 3-16-year-old children’s schooling status. In addition to patterns of enrollment both nationally and across states, ASER data provides insights on the age distribution of children in each grade and enrollment patterns in pre-primary institutions and schools. ASER also provides evidence on basic reading and arithmetic levels of children aged 5-16 in rural India. Information on parental education and household characteristics is also collected.

ASER 2024

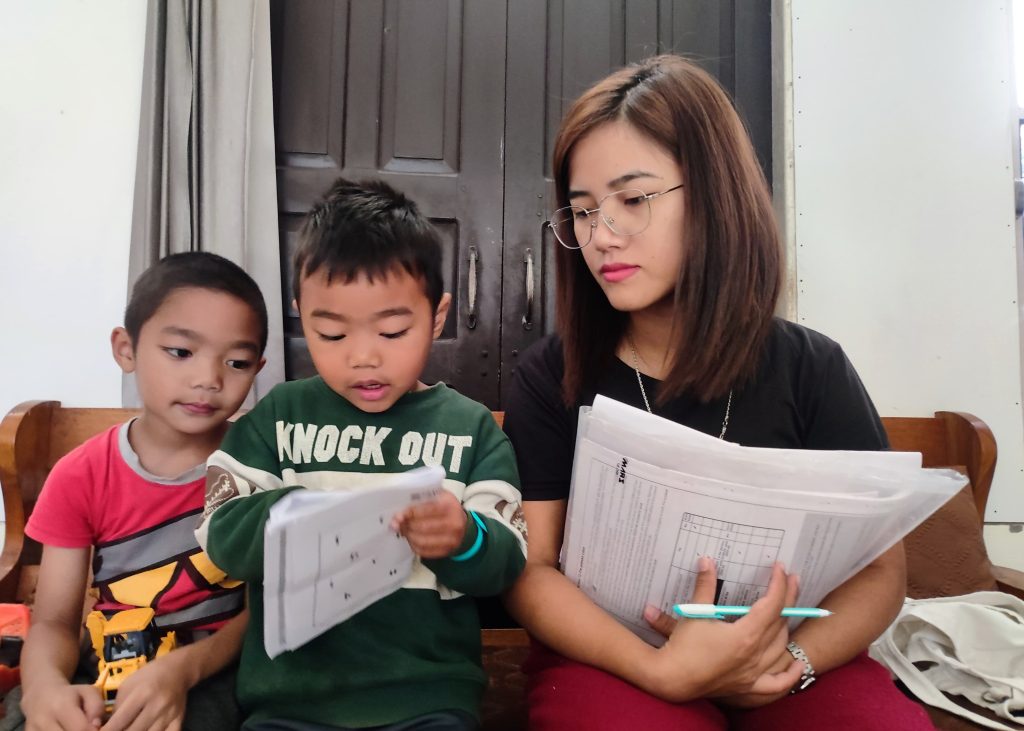

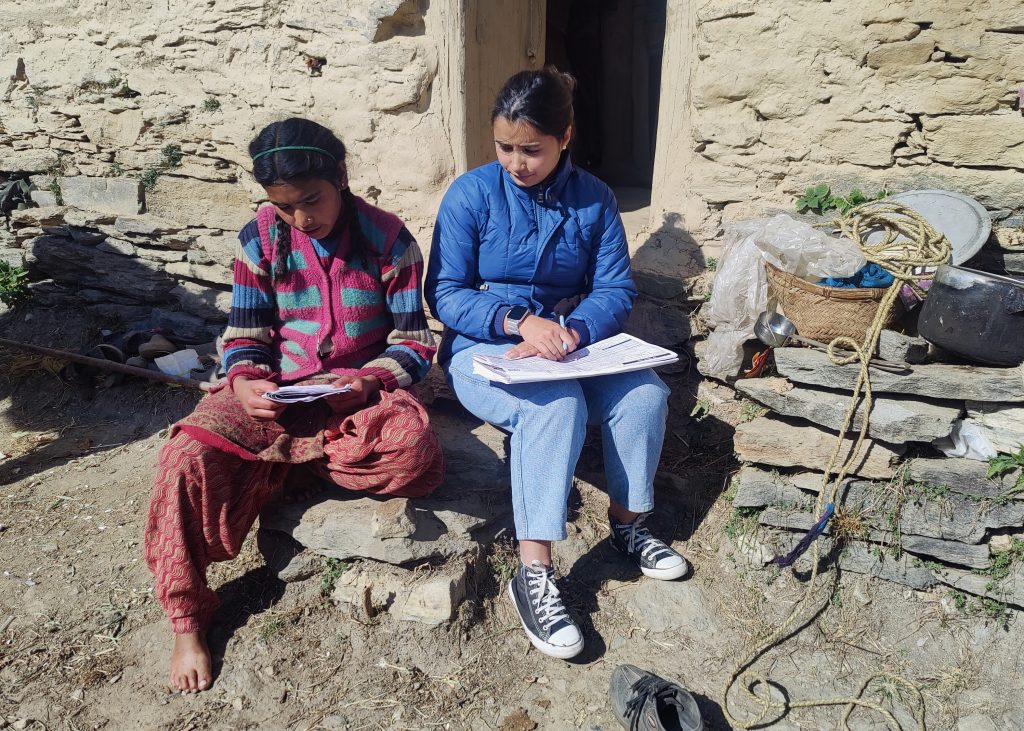

ASER 2024 reached over 650,000 children across more than 600 districts in 26 states and 2 Union Territories in India. The 2024 survey retains the core elements of the ASER architecture: it is a sample-based rural household survey done by local organizations and institutions in each district, conducted one-on-one with each sampled child using simple and easy to administer tools and formats. As always, the survey assesses the basic reading and arithmetic abilities of 5-16-year-olds. For young children, the survey tracks participation in early childhood education. For older children aged 14-16, for the first time, the survey generates representative estimates of digital access, usage, and skills.

Frequently asked questions

ASER is conducted by volunteers from local partner organisations in each district. A wide range of institutions partner with ASER each year. These include universities and colleges, non-governmental organisations, and government institutions, among others. For example, in 2024 ASER was conducted by students from the District Institutes of Education and Training (DIETs), the government teacher training colleges, in about 215 districts. The process of finding, training, and monitoring ASER partners and volunteers is led by ASER Centre, the research and assessment unit of Pratham Education Foundation.

ASER is a rural survey. Urban areas are not covered. ASER usually attempts to reach every rural district of the country (although in some years certain states have been excluded for logistical and security reasons, such as Jammu and Kashmir in 2010, Arunachal Pradesh in 2013, Goa in 2022, and Goa and Manipur in 2024). However, every year ASER is unable to reach some rural districts. Generally, this is due to natural disasters, situations of unrest or conflict in the district. In 2024, ASER has reached over 600 districts of the country.

A close look at any ASER table of results shows that even within a single grade, children’s ability to read or do simple arithmetic varies enormously. Teaching from a grade level textbook will not work for children who are not at that level. In traditional classrooms, these children get left further behind as they move to higher grades. Improving children’s foundational learning levels requires an understanding of what children are currently able to do, so that teaching methods and materials can be designed to enable them to start from their current level and build towards the learning levels appropriate for their age and grade.

ASER data tells us where most children are getting stuck, so that resources can be allocated accordingly. Children from different grades who are at the same level of reading ability can be grouped together. This approach has come to be known as ‘Teaching at the Right Level’, in other words teaching children based on what they know and can do, rather than based on their age or grade. Many schools and education programs already implement this approach, and so do several state governments. Understanding children’s current learning status is the critical first step, and the ASER results provide this. If data is required for a specific geography or group, ASER tools and testing process can easily be used to generate this understanding for any class, school or group of children. Check out ‘Do it yourself ASER’ here.

ASER has had a major influence in bringing the issue of learning to the centre of the stage in discussions and debates on education in India. In 2005, when ASER began, most people, from parents to government functionaries, were concerned with getting children into school. The assumption was that if children were in school, they must be learning. Today, the fact that large proportions of children are not learning even the basics is widely recognised. For example, ASER has been cited in major Government of India documents such as the XI and XII Five Year Plan and the Economic Survey of India. Moreover, ASER data has been referenced in various reports such as: NITI Aayog’s Three Year Action Agenda for 2017-18 to 2019-20, and World Bank’s World Development Report 2018, ‘How Learning Continued during the COVID-19 Pandemic’ by OECD and the World Bank in 2022, Global Education Monitoring Report 2022, SDG 4 Data Digest: Data to Nurture Learning, and Learning Outcomes at the Elementary Stage by NCERT to making the learning crisis visible and advocating for remedial steps towards improving learning outcomes. Over the years, ASER data has also been referenced in 105 parliamentary questions demonstrating its significance in policy discussions. Many state governments are now implementing their own learning assessments, sometimes using tools very similar to the ASER tools and other times in collaboration with ASER Centre. A great deal remains to be done to ensure that every child in India is in school and learning well. But the first step is for the problem to be widely recognised. The second step is to have reliable evidence on the nature and extent of the problem. Only then can viable solutions be found.